Report #7: Can Housing First Beat Fentanyl, Meth, and Psychoses? The Crisis of Chronic Homelessness and the Case for Heterodox Housing Policy

George Galster, Hilberry Professor of Urban Affairs and Distinguished Professor, emeritus

Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48202

Residence: Portland, OR 97209

The Growing Crisis of Chronic Homelessness and the “Housing First” Response

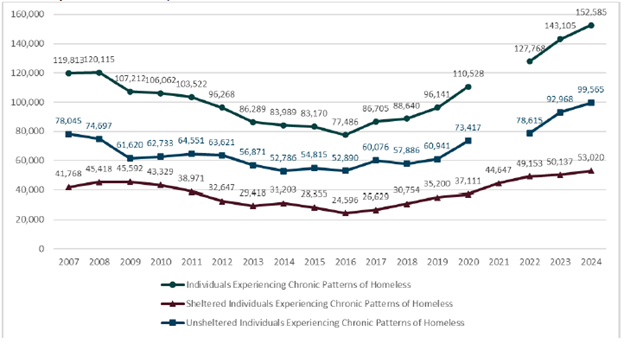

The most recent point-in-time count of homelessness, sponsored by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD, 2024), reveals a distinct turning point in the trajectory of chronic homelessness. After a decade of steady progress, since 2016, the number of chronically homeless individuals—particularly those that are unsheltered—has been dramatically increasing in the U.S. and in Multnomah County. The preliminary data for the 2025 point-in-time count confirms this trend.

Why this turning point in chronic homelessness? It cannot be fully explained by the usual suspects in homelessness discussions (e.g., rents, wages, subsidized housing, permanent supportive housing), since none of them show an inflection point around 2016. This distinctive turning point in chronic homelessness can best be explained by the arrival of cheap, highly addictive fentanyl and the “new,” more psychosis-inducing methamphetamine in American street drug markets around 2013-2014 or somewhat later, depending on geography. This expansion in drug use also corresponds with steadily increasing numbers of people suffering from severe mental illnesses that are inadequately treated.

HUD Point-In-Time Estimates of Individuals Experiencing Chronic Homelessness, 2007-2024

We know that chronic substance abuse disorders and severe mental illness can be both causes and consequences of homelessness; I need not debate here the relative magnitudes of these two forces. My point is that we clearly face an exploding substance abuse disorder / mental illness dual crisis that manifests itself in the upwelling of chronic, unsheltered homelessness. The goal of a humane community should be not to simply “get these people off the streets,” but to help them secure and maintain mental health, freedom from addiction, and reintegration into society.

The dominant approach in Multnomah County and much of the US for fighting chronic homelessness has been “Housing First” (HF). This strategy involves placing homeless individuals as quickly as possible into permanently subsidized housing with no requirements for them to engage in behavioral health support prior to or after placement. Ideally, an array of case management and other support services aimed at sustaining individuals in their homes and improving their health, behavioral health, and other outcomes are available to people in their homes, upon request.

There are many other psychosocial approaches for addressing the mental health and substance abuse disorder challenges of homeless people, which generically go by the rubric “Treatment First” (TF). These non-pharmaceutical interventions include: cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, contingency management, group and family therapies, skill-building, chronic care model-based intervention, cognitive remediation therapy, contingency management, frailty intervention, mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement program, psychiatric rehabilitation model-based intervention, relaxation response training, self-compassion training and strengths-based intervention, and case management. It is important to note that these psychosocial approaches can be used in combination with HF if the client wishes. TF, on the other hand, starts with homeless populations drawn from shelters, transitional housing, or residential treatment/rehabilitation centers who wish to be treated. Permanent housing is offered only when the treatments lead to the client being “housing ready.”

Is Housing First the Most Effective Approach for the Mental Illness/Substance Abuse Disorder Crisis among the Chronically Homeless? A Hard Look at the Evidence Base

HF has become the dominant orthodoxy because it has been touted as an “evidence-based” strategy. A close examination reveals that the only strong evidence is that HF provides stable shelter; as for tackling the chronic homeless crisis more effectively than other options, the evidence base is shaky.

The most extensive, oft-cited evidence base in support of HF is the set of studies evaluating the impacts and cost-effectiveness of the NY/NY III permanent supportive housing initiative, a longstanding program typically viewed as the archetype of what HF should be. Gouse et al. (2023) recently reviewed this body of evidence and drew a conclusion that encapsulates the conventional wisdom:

NY/NY III was established to provide permanent, stable housing with support services to New Yorkers experiencing chronic homelessness who suffer from complex medical and behavioral issues, including substance use, serious mental health issues, and chronic health conditions. Our findings conclude that placement into NY/NY III housing was associated with improved physical and mental health outcomes and increased housing stability.

The “gold standard” for scientifically rigorous medical research is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). In an RCT, the “treatment” under investigation is administered to individuals who are randomly chosen from the set of study participants; the remaining participants are either treated with another intervention or used as a control group. A closer inspection of how the NY/NY III program was operated and evaluated indicates that it was not a random control trial, and raises serious questions about the validity of the above conclusions.

All studies of this intervention are based on a common quasi-experimental method for impact evaluation: measuring outcome differences between the treatment group (HF participants) and a control group (HF-eligible, but non-participants receiving TF/TAU) who were matched with the treatment group by their similar observed characteristics as recorded in administrative databases. Non-profit service providers contracted with the city to provide HF chose the people on the eligibility lists to whom they would provide supportive housing, based on in-person interviews. This interview (in addition to applicants’ administrative data) provided the perfect opportunity for contractors to “cherry pick” those who they deemed most likely to succeed; it clearly would be in the organization’s best interests to do so. Crucially, what individual characteristics the service providers observed during these interviews were not recorded in administrative data. Thus, when researchers matched treatment and control groups using administrative data on individual characteristics, they were unable to match on characteristics that could be expected to systematically bias outcomes in favor of the treatment group. In sum, the touted evidence base of the archetypal HF program is likely based on an unrepresentative sample of participants who were selected by those who had the motive and opportunity to “cherry pick” those receiving HF and whose idiosyncratic characteristics could neither have been observed nor corrected for by the researchers.

In the last six years, four peer-reviewed scholarly papers have been published that comprehensively examine actual RCT research on treating chronically homeless individuals in the U.S. and Canada with HF. All conclude that the reputed mental health and substance abuse disorder benefits of HF are exaggerated, even though housing stability has been enhanced. Baxter et al. (2019) examined all RCTs related to four different HF initiatives’ impacts on homeless individuals with mental illness, substance abuse disorder, and/or chronic physical illness. Their analysis revealed that after 18-24 months of treatment, there were no statistically significant differences between the HF-treated group and “Treatment as Usual” (TAU) control group in: (1) changes in self-reported mental health; (2) changes in self-reported physical health; and (3) time spent hospitalized. HF participants did, however, exhibit statistically significantly fewer numbers of hospitalizations and emergency department visits and, of course, improved housing stability. Peng et al. (2020) concluded, “HF programs produced similar changes in physical and mental health and substance use when compared with TF or TAU approaches; that is, HF yielded no additional health benefit” (p. 408). Aubrey et al (2020) conclude (p. e342) that permanent supportive housing increased housing stability but had no measurable effect on the severity of psychiatric symptoms or substance use. Gouse et al. (2023: 3) conclude, “Overall, existing literature supports the conclusion that permanent supportive housing causes greater housing stability compared to other models and may contribute to improvements in mental and physical health and substance-use behavior, albeit to a similar degree as other treatment models” [emphasis mine].

Two peer-reviewed scholarly papers have also been published that comprehensively examine RCT research on Treatment First (TF) interventions with chronically homeless individuals in the U.S. and Canada. Hyun, Bae, and Noh (2020) concluded that some psychosocial TF approaches showed significant effects on anxiety and the mental health status of homeless adults, but not on their depression, psychological distress, or self-efficacy. Specifically, they suggested that relaxation response training may be effective in improving anxiety and mental health status, and cognitive behavioral therapy may reduce anxiety. Wang et al. (2019) concluded that cognitive behavioral therapy produced improvements in depression and substance use outcomes among homeless youth, and family-based therapies also decreased their substance use. Although these results indicate that TF in general is not a panacea for mental illness and substance abuse disorder challenges of homeless adults and youth, it is also clear that certain types of psychosocial approaches appear especially promising. Indeed, the evidence suggests that they demonstrate just as much efficacy in altering mental illness and substance abuse disorder outcomes for the homeless as have been demonstrated by RCTs of HF.

In sum, just because the evidence shows that HF can “end homelessness” does not imply that it is the most powerful weapon against severe mental illness and substance abuse disorders currently afflicting the chronically homeless. And this does not take into account the property damage, staff burnout and attrition, and triple-digit insurance increases that providers experience when practicing HF without first addressing behavioral health problems. These costs and their implications are detailed in Central City Concern’s recent report.

I therefore must agree with the assessment of Waegemakers, Schiff, and Schiff (2014): “A review of the research indicates that the success of ‘Housing First’ relies more on political support than widespread scientific evidence of ‘best practices’ (p. 80).

What Does this Evidence Mean for Policymakers?

My closing comments are directed primarily toward Multnomah County Commissioners and Continuum of Care policymakers who believe that HF is the ONLY way to end homelessness and is the singular strategy that should be pursued. Camouflaged behind the misguided claim that it is “evidence-based,” HF has become accepted as a matter of faith, a goal that must be pursued myopically. Comprehensive data collection and rigorous, timely evaluations of programmatic outcomes that could guide mid-course corrections are eschewed because the “best approach” is pre-ordained. Alternative strategies are ignored, and dissent quashed.

I want to make it clear that I am not an opponent of HF as a vital part of a comprehensive, coordinated strategy to end homelessness. Rather, I am opposed to HF as the only strategy to end homelessness instead of a more heterodox strategy including HF and TF. This balanced strategy is what the evidence supports. We must move toward a more diversified set of options that can better tailor treatments to individual circumstances—and build the requisite integrated case management data systems and human and physical resources in the public health domain to support such—if we are to fight the symbiotic scourges of chronic homelessness, mental illness, and substance abuse disorders successfully.

References

This report is a condensed version of Professor Galster’s paper: Galster, G. (2025). Can Housing First Beat Fentanyl, Meth, and Psychoses? The Crisis of Chronic Homelessness and the Case for Heterodox Housing Policy [forthcoming in Housing Policy Debate] Link to Original Paper

Aubry, T. and 14 others. (2020). Effectiveness of permanent supportive housing and income assistance interventions for homeless individuals in high-income countries: A systematic review. Lancet Public Health, 5(6): e342-360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30055-4

Baxter, A.J., Tweed, E.J., Katikireddi, S.V., & Thomson, H. (2019). Effects of Housing First approaches on health and well-being of adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73(5), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2018-210981

Gouse, I., Walters, S., Miller-Archie, S., Singh, T., & Lim, S. (2023). Evaluation of New York/New York III permanent supportive housing program. Evaluation and Program Planning, 97, 102245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2023.102245

HUD (2024). The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Washington, DC: US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Available at: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/ahar/2024-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us.html

Hyun, M., Bae, S.H., & Noh, D. (2020). Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized control trials of the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for homeless adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76, 773–786. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.wayne.edu/10.1111/jan.14275

Peng, Y. & 11 others. (2020). Permanent Supportive Housing With Housing First to Reduce Homelessness and Promote Health Among Homeless Populations With Disability: A Community Guide Systematic Review. Journal of public health management and practice, 26 (5), 404-411. DOI: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001219

Waegemakers Schiff, J. & Schiff, R.A.L. (2014). Housing First: Paradigm or program? Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 23(2), 80-104. doi: 10.1179/1573658X14Y.0000000007

Wang, J.Z. and 7 others (2019).The impact of interventions for youth experiencing homelessness on housing, mental health, substance use, and family cohesion: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 19:1528. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7856-0

Woodhall-Melnik, J.R. & Dunn, J.R. (2016). A systematic review of outcomes associated with participation in Housing First programs. Housing Studies, 31(3), 287-304. doi:10.1080/02673037.2015.1080816