Shelter, Housing Assistance, and Supportive Housing

The city and county fund various shelter and housing programs to reduce homelessness. In general, the data provided to evaluate these programs is missing, incomplete, contradictory, or confusing. Nevertheless, in this report we try to distinguish between the major types and attempt a cost-benefit analysis. We welcome comments and corrections from our readers.

“Shelter” is a place for a homeless person to temporarily get off the street with a roof, bed, toilets and showers and a place to put their possessions.

“Housing assistance” encompasses a number of programs and services to help individuals and families secure and maintain stable housing, including rent assistance, rapid rehousing, eviction prevention, and payment of utilities, application fees, moving costs.

“Supportive housing” combines temporary or permanent housing with support services such as healthcare, including mental health and substance abuse treatment, and job training.

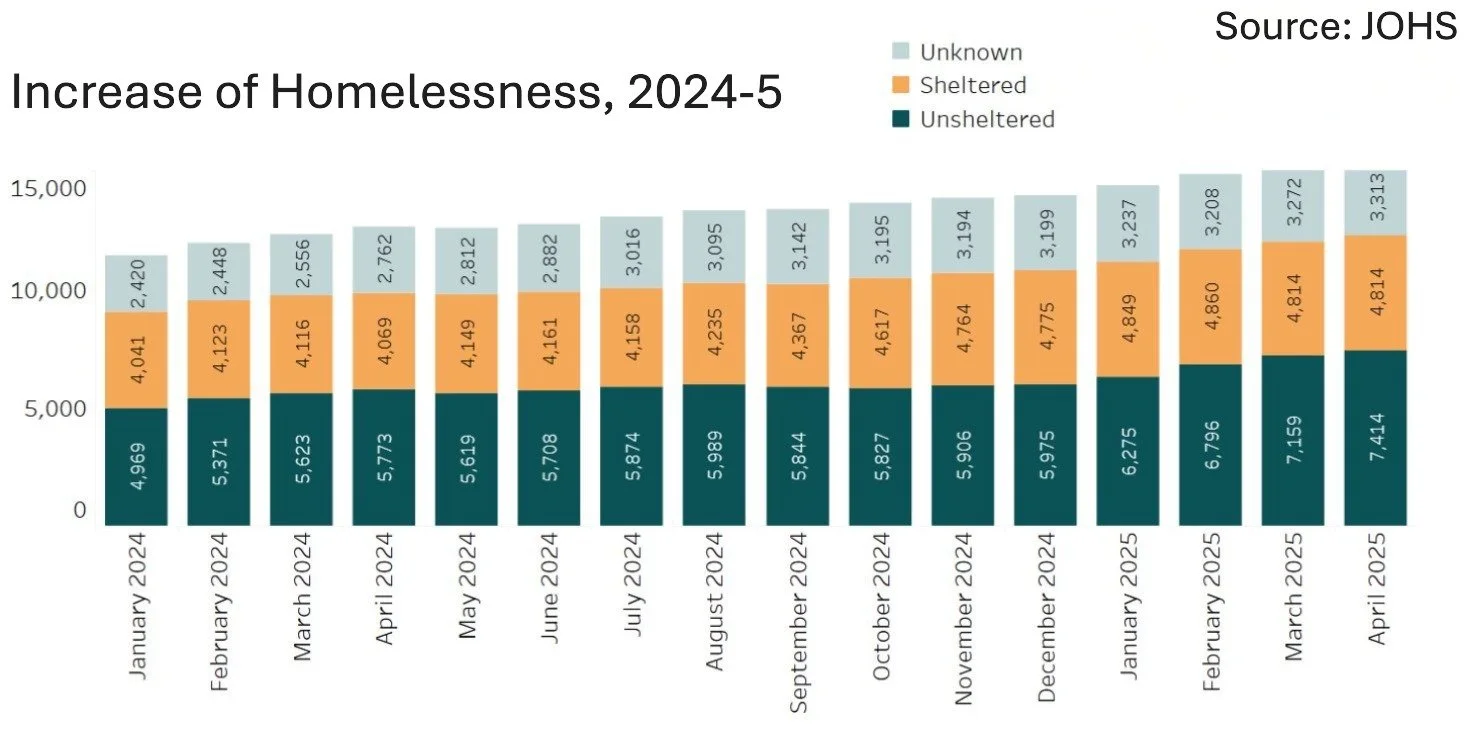

All three of these housing solutions are implemented in a context where the number of homeless, both temporarily sheltered and unsheltered, has continued to increase in Multnomah County in each of the last five years. Each should be evaluated for cost per person served and effectiveness in aiding the homeless receive treatment and to achieve permanent housing, as well as raising the quality of life in the most impacted areas of our city. [i]

Shelter

Mayor Keith Wilson has shifted priorities to focus on creating enough shelter beds as part of his goal to end unsheltered homelessness in Portland. His FY2025-26 proposed budget included $28 million to address homelessness as follows: [ii]

● Adding up to 1,500 overnight shelter beds at a cost of $15,309,000. 15,309,000/1500= $10,206 per person per year.

● Adding new day centers with a combined capacity of 600 guests per day at a cost of $11,974,920.

● Adding new space where 1,200 people can store their belongings for the day at a cost of $216,000.

The cost of the additional 1,500 beds should include the day center and storage space costs, a total program cost of $27,499,920 or $18,333/shelter bed/year.

If increasing shelter beds is tied, as Mayor Wilson intends, to a public sleeping ban, it does address the quality of life on the city’s streets by decreasing unsheltered homelessness. However, shelters alone, without additional support, have not been effective in moving the homeless into permanent housing. A success rate of 12% for moving people from homelessness on the streets to temporary or permanent supportive housing in Multnomah County is often cited.

According to JOHS there are currently about 4,800 sheltered homeless and 7,400 unsheltered homeless. The mayor plans to add 1,500 beds for the 7,400 unsheltered, possibly expecting many will leave town if required to enter shelters.

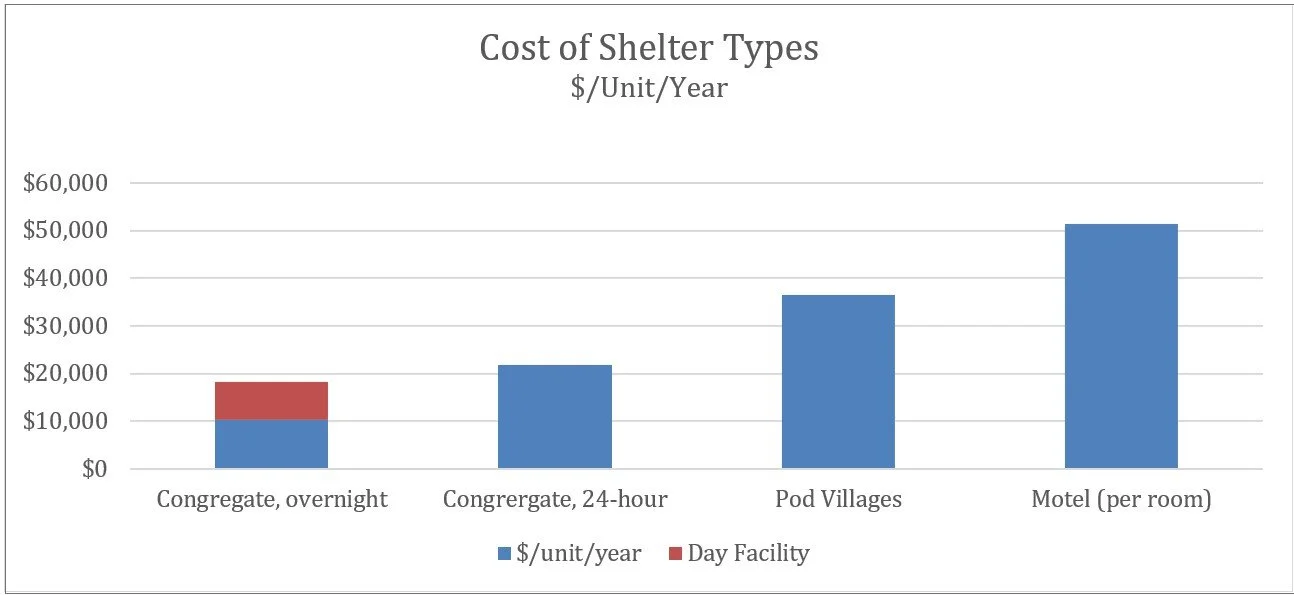

Alternative shelters such as pod villages and motels were more successful than congregate shelters but were also more expensive. They have a reported success rate of 47%, significantly better than congregate shelters, but it is not clear how much of that is due to better living conditions and a less challenging client base. 24-hour congregate shelters cost about $21,900/bed/year, pod villages cost about $36,500/bed-year, and motels cost about $51,500/room/year (rooms can have up to 3 or 4 people in a family).

Although adding more shelter beds is beneficial, JOHS data shows a significant shortfall will remain. Without detox and stabilization support in shelters, people experiencing homelessness are unlikely to transition from shelters to supportive housing.

Housing Assistance

In 2025, JOHS is projected to spend $23,800,000 to serve 3,550 individuals, or $6,704/person, with their “eviction prevention” service, which helps people pay a few months’ worth of rent while the recipients get on their feet. No data was provided on outcomes, and ex-Commissioner Sharon Meieran has raised trenchant criticism of the county’s rent assistance programs.

A similar program, the Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) rental assistance to Oregon Health Plan members, served 517 people at an average cost of $2,225 per month while enrolled. The program is run by the state.[iii]

One Multnomah County program in the 2024 budget allocated $61,500,000 to rental assistance and housing case management for 7,142 people to avoid eviction at a cost of $8,611/person.[iv]

All of these may be worthwhile goals and efficient in the expenditure of funds per person served, but it is unlikely that even half were actually “from the street.” It seems that policy makers avoid the most difficult subset of the homeless, the “chronically homeless,” which comprises 50% or more of the homeless in Multnomah County.[v]

Supportive Housing

In one program, Multnomah County received $60 million funded by Metro for permanent supportive housing and served 2,322 people at a cost of $25,840/person.[vi]

In fiscal 2024, Multnomah County assisted 2,890 people through a rapid rehousing program intended to help individuals and families experiencing homelessness transition from shelters to permanent housing at a cost of $48,600,000, approximately $16,816 per participant. While the county provides details on participants’ race, ethnicity, disability status, and gender identity, there is no information regarding their previous living situations, placement locations, or long-term outcomes.

Multnomah County in 2024 also used about $15 million in Metro Supportive Housing Services (SHS) dollars to expand addiction treatment services for people living with substance use disorders, leading to 105 additional recovery-oriented, stabilization, and transitional housing beds at a construction cost of $142,857/bed.[vii]

In the nonprofit sector, Central City Concern provides single room occupancy (SRO) transitional or permanent supportive housing units that may start at $464.00/month ($5,568/year), while studio apartments can start at $932/month ($11,184/year). It is unclear what services are provided, however.[viii]

The “chronically homeless,” about 50% of Multnomah County’s homeless, often cannot afford any rent, and their need for support services is high.[ix] In 2018, the County and County estimated that such supportive housing for 2,000 people would cost between $592 and $640 million over the years, with annual costs of $43 million to $47 million after that.[x] This includes not just the housing itself, but also supportive services like rent assistance, behavioral health, and addiction services, and would cost $30,000 to 32,000/year. Adjusting for inflation brings it to about $38,000/bed/year in 2025 dollars.

Recommendations

If the direct costs of homelessness in Multnomah County in 2024 were over $800mm and the April 2025 number of homeless was 15,541, we are currently spending $53,922/homeless individual/year. We can do better to address the needs of the homeless in our city and county and vastly improve the quality of life for all.

Shelter: In theory, we support Mayor Wilson’s plan to increase temporary shelter beds. At a cost of $18,333/shelter bed per year, this is a good step toward decreasing public camping and improving quality of life at the street level. But for it to work, the county must step up and improve the flow of homeless individuals from shelters to treatment to housing. Today, only a small minority of the people going into supported housing are from shelters, indicating that the currently homeless are not being served well. We need a comprehensive system that moves them from shelter to services (often detox and stabilization), to supported housing with the level of support the individual needs--the chronically homeless addict coming out of detox and stabilization will require far more support than the recently homeless and sober.

Housing assistance programs are important in preventing more people from falling into homelessness, although not directly connected to moving currently homeless people off the street into housing. They focus on keeping “at-risk” people from becoming homeless, which, in theory, should be the most cost-effective means of lowering unsheltered homelessness. However, there is no data indicating how many at-risk individuals would become homeless without assistance. In an era of limited budgets, we need to know how cost-effective these programs really are.

Supportive housing with an average cost in Multnomah County of approximately $37,000 per individual has the best record for helping the homeless, particularly the chronically homeless, exit the street into permanent housing, and as Central City and Denver have shown, can be done cost efficiently over time. However, the level of support must be calibrated to the individual’s needs, which in many cases will likely cost more.

FOOTNOTES

[i] We have not included “affordable housing” here in that such programs are not directed toward the currently homeless. We will, however, research what affordable housing means, what it costs and who it serves in a future report.

[ii] https://www.portland.gov/mayor/keith-wilson/news/2025/1/27/mayor-wilson-presents-blueprint-end-unsheltered-homelessness

[iii]https://www.healthshareoregon.org/health-equity/housing-pilot

[iv] https://multco.us/news/news-release-multnomah-county-helped-2469-people-leave-homelessness-second-half-2024#:~:text=NEWS%20RELEASE:%20Multnomah%20County%20helped%202%2C469%20people,to%20avoid%20eviction%20with%20emergency%20rent%20assistance

[v] https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/coc-esg-virtual-binders/coc-esg-homeless-eligibility/definition-of-chronic-homelessness/

[vi] https://multco.us/info/fy-2024-adopted Budget#:~:text=This%20includes%20$74%20million%20in,programs%20serving%20people%20experiencing%20homelessness

[vii] https://hsd.multco.us/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Formal-FY-2024-SHS-Annual-Report-Digital-Ready-1.pdf

[viii] https://centralcityconcern.org/housing-location/cedar-commons/

https://www.portland.gov/phb/construction/cedar-commons

[ix] https://hsd.multco.us/data-dashboard/

[x] https://www.wweek.com/news/city/2018/09/07/one-cost-estimate-to-solve-portlands-homelessness-problem-640-million-over-10-years/